This image of a buck appears with my monthly column in the current print edition of the Ellsworth American. To read the column about the history and ramifications of wearing (and not wearing) “hunter [blaze] orange” clothing during hunting seasons, use this link:

It’s time to see one of our many soothing local scenes and wonder why it soothes. Here’s a glimpse of the near-mountain called Blue Hill as it looms above a reflective Blue Hill Bay last week:

Studies show that scenes with water, often called "blue spaces" by researchers, are especially beneficial for mental health due to our evolutionary development. For many people, apparently, simply gazing at bodies of water – or images of them – can lower their heart rate and blood pressure and reduce levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Nature’s abundant “cool” blue and green colors historically have been associated with the evocation of tranquility in people. Seeing a calm, reflective, watery surface has been found to make people pause and reflect on their own thoughts and emotions while also feeling reconnected to nature. These feelings, in turn, can reduce anxiety and stress and lead to feelings of peace and a better mental balance.

Of course, I’m not qualified to say that the reported psychological observations are accurate for anyone other than me. But I do know tranquility when I feel her, and she comes silently to me sometimes when I visit scenes like this. (Image taken in Blue Hill, Maine, on October 3, 2025.)

The common loon in winter is drab. And that’s okay with the loon. Coastal bald eagles now hang around all year and prey on what they can find and catch. The loon that you see here was transitioning yesterday to its winter attire:

In the summer, when they’re trying to mate, loons are fashion plates wearing birdland’s version of Giorgio Amani formalwear: white-spangled, rich black plumage, ruby eyes, shiny black bill, and a flickering iridescent necklace:

Leighton Archive Photo

In their winter wear, when they’re trying to survive, they ditch the startling red eyes, black and white attire, and iridescent jewelry and don grays and whites that have the brilliance of dishwater.

On a gray winter’s day, you’d hardly notice a loon fishing alone as they do, very low in the water, disappearing and appearing without hardly a sound – except when it can’t help being loony and emits a startling winter wail, then laughs tremulously at itself. (Primary image taken in Little Deer Isle, Maine, on October 7, 2025.)

Here you see October’s full moon rising over Blue Hill and Jericho Bays while the sun was setting yesterday evening. Haze and particles in our atmosphere distorted it and made it appear reddish until it broke through the pollution band.

This visit by our faithful companion is a three-fer: it’s the Harvest Moon, because it’s the full moon closest to our autumnal equinox; it’s the Hunter’s Moon, because that’s the traditional name given to the October full moon, and it’s a Super Moon because it’s close to its lowest orbit of Earth (its “perigee”). We’ll have Super Moons in November and December, also.

The Harvest and Hunter’s Moon designations reportedly are the most popular names that this month’s moon was called by northeastern Native Americans (Algonquin, often), as adopted by early European settlers and collected by the Farmers’ Almanac.

However, the October moon has other historic Native American names that vary geographically. For example, Maine's Abenaki people referred to it by various names depending on the month’s events, such as the Dying Grass Moon or the Travel Moon.

(Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on October 6, 2025.)

Fall warblers are coming through in good numbers now.

I’m a considerably-less-than-awesome birder when it comes to identifying warblers, especially dull-hued fall warblers. They seem to have a habit of staying mostly in the leafy shadows. And, they’re usually only about the size of a Snickers® candy bar or standard playing card. And, the damn things hardly ever stay still when I try to focus binoculars or a long lens on them. And, and, and …. (Why can’t warblers be like pushy black-capped chickadees?)

You might appreciate my situation by trying to find the warbler that’s staring straight at me (hence, you) in this photograph taken Saturday:

I don’t see any really good identifying marks from that perspective; stripes are common to many types of warblers. However, as usual, he didn’t stay still long and I managed to get a privacy-invading shot of him and his bold butt:

That dab of yellow on his rear (and a little on his side) make me believe that he’s a Yellow-Rumped Warbler and that he’s on his way with his kind to the southern states, Mexico, or Caribbean. Bon voyage, you little devil! (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on October 4, 2025; sex assumed.)

For some of us, a fine fall morning at high tide on Maine’s Down East coast can be more satisfying than the best Scotch. As you may know, this is the old red boat house at Conary Cove just doing its job of making passers-by feel better.

(Images taken in Blue Hill, Maine, on October 3, 2025.)

Above, you see FROLIC yesterday, the last sailboat in Great Cove. Below, you’ll see VULCAN visiting the Cove yesterday. If anyone wants an illustration of the difference between elegance and inelegance, there it is. Beauty and strength are welcome, but often come separately.

FROLIC is a Luders 16. That is, her design is by the renowned naval Architect Alfred E. (Bill) Luders and she’s 16’4” long at the waterline. She’s a racer owned by a neighbor and probably will be “taken out” for winter storage soon.

VULCAN is a moorings service vessel owned by Brooklin Marine, LLC. Her crew installs, removes, maintains and repairs moorings and mooring equipment. Her crew apparently was replacing the large, summer ball buoys that float on mooring chains with slim, winter mooring sticks (long, thin, vertically-oriented buoys that are better at withstanding ice).

As with most of life, it takes all kinds. (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on October 4, 2025.)

As you see, Mount Desert Island was under celestial shark attack on Wednesday. However, the large island survived and its Acadia National Park reportedly is remaining open despite a federal government shutdown. That’s the good news.

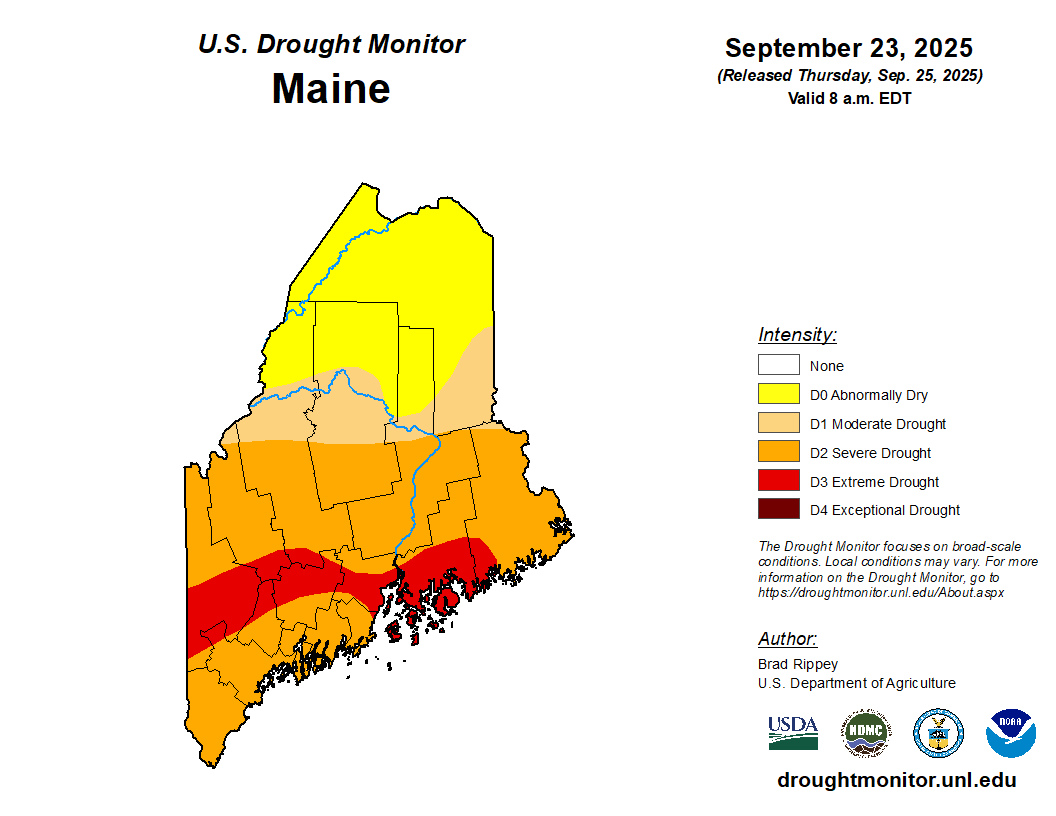

The bad news is that we’ve been having a lot of beautiful weather of the type that you see here. Yes – you read that right; that’s bad. We need about a week of steady rain. We remain in an extreme drought and the possibility of catastrophic wildfires in our extensive woodlands is real. See the latest official map:

(Photograph taken from Brooklin, Maine, on October 1, 2025.)

The most important news about this September is that it did not relieve Maine from severe and even extreme drought. It was a crisp, beautiful, exhilarating month, yes. But dangerously so. Maine is the most forested state and much of it is experiencing fire hazard conditions. Here’s the latest official map:

But, enough of this gloom! You’re expecting some September beauty and you’re going to get a lot — maybe too much — of it in the following Postcards, which show that “We’re (Still) Having a Wonderful Time and Wish You Were Here.”

As usual, we start with the iconic views of the four Down East scenes that we monitor for you each month: The view from Brooklin’s Amen Ridge of Mount Desert Island, Maine’s largest island; the “Harbor Island House” overlooking Brooklin’s Naskeag Harbor; the old red boat house in Blue Hill’s Conary Cove, and Blue Hill, the near-mountain itself, as viewed across Blue Hill Bay:

Despite the dryness, walking through the dappled light and balsam scent of a mixed-wood forest on a crisp September day still can be sanity-saving. The slow rhythms of song birds were replaced by the percussion of hairy and piliated woodpeckers and the constant complainting of red squirrels.

Our ponds were lower and our streams were slower, but they retained their vibrancy. The painted turtles, beavers and dragonflies didn’t seem to be concerned about the loss of water, which may be a good sign:

As for the flora of September here, the standout trees were the centurian apple trees that still bear tempting fruit on almost leafless branches; the plum trees with indescribably deep red leaves; mountain ashes, some with red and some with orange berries; sugar maples starting to show fall colors, and fruited crabaple trees:

For bushes and ferns, the eye-catching prizes go to the viburnum leaves and berries; beach rose flowers and their hips, and cinnamon ferns, all of which became transformed in September:

The representative wildflowers of September included Queen Anne’s lace in its caged and galaxy forms; the many varieties of goldenrod, much of which became “grayrod” by the end of the month; asters that didn’t care where they called home, and sea lavender in and out of water:

In the gardens, we saw the last of the tiger lilies, poppies, petunias, and clematis in September. But, gladiolas still were putting up a good fight at the end of the month and chrysanthemums and gourds were becoming available:

Our fallow fields were thick and full of the browns and whites of fall grasses, sedges, and wildflowers before our annual September mowing:

After the mowing, white-tailed deer found new hiding places among garden grasses and ferns; snowshoe hares gorged themselves on the shorter grass; monarch and white admiral butterflies and other pollinators patrolled the flowers along the uncut edges, and grasshoppers, fall crickets, and tiny field toads were exposed to marouding wild turkeys:

It’s worth highlighting the September caterpillars that turned themselves into this year’s “super generation” of stronger monarch butterflies. These miraculous, longer-living monarchs started their dangerous migration from Maine to Mexico in September. We wish them a safe trip.

Another vulnerable species is the great blue heron, which usually migrates south, but increasingly has been overwintering here as our years get warmer:

Sometimes its easy to forget the beauty and importance of our resident birds, especially our many herring and ring-billed seagulls. They’re among nature’s toughest species and best flyers, not to mention their having a fancy for harmful European green crabs that hide in the rockweed:

The September coast is visited by other, larger migrators in the summer and fall. They come in the form of classic windjammers that sometimes gather together for a rendez-vous, but usually take tourists on special, multi-night coastal cruises. Here are some that visited Brooklin’s Great Cove in September:

American Eagle

Angelique:

Grace Bailey

Heritage and J.&E. Riggin:

Stephan Taber

Lewis R. French and Ladona:

On the working waterfront, the fishermen and their vessels in Naskeag Harbor seem to have been very busy tending lobster traps in September. When the fishing vessels return to their moorings, they complete the picturesque scene.

Up the coast a mile or so, we have another picturesque harbor that was busy in September. It’s Center Harbor, the port for many recreational boats and the home of the renowned Brooklin Boat Yard:

Between Naskeag Harbor and Center Harbor there lies Great Cove, where the also-renowned WoodenBoat Publications headquarters and WoodenBoat School are located. The Cove is very busy all summer. The School ends its boatbuilding and other classes in September. Sailing classes end early in the month, but faculty can take out a boat for a sundown sail after work. By the end of the month, though, all boats usually have been brought ashore, cleaned, and stored for the winter.

Finally, we look to the sky. The September moon, which often is called the Corn Moon or Corn Harvest Moon when full, was spectacular almost all month, perhaps due to the month’s relatively dry and cool, clearer air.

The cleaner atmospheric conditions and our changing views of the sun in September combine to start the colder months’ “sundown afterglow season.” That’s when we begin to see increasingly spectacular sights of coastal waters, such as Great Cove:

(All photographs in this post were taken in Down East Maine during September 2025.)

Here you see FOX at rest in Great Cove on Sunday, the only sailboat in the WoodenBoat School fleet remaining there then. The School’s year ended last week and FOX was scheduled to be pulled out of the water yesterday and tucked into storage with the rest of the fleet until next year’s classes.

But some fortunate sailors have everlasting memories of sailing on FOX and her sisters. And others will be able to have those memories created in next year’s classes. Here’s a Leighton Archive image of FOX being sailed and creating memories:

Leighton Archive image

FOX is a Haven 12 ½ daysailer designed by Brooklin Boat Yard’s Joel White in 1985. The Havens are a practical adaptation of perhaps the most classic of small sailboats, the Herreshoff 12 ½ (foot long at the waterline) daysailer. The Herreshoff was designed by the dean of sailboat designers, Nathanael Herreshoff, in 1914 as a safe, high-performing training boat.

The principal difference between the Haven and the Herreshoff is that the Herreshoff has a relatively large, fixed keel and the Haven has a removable centerboard for shallow water access and easy transportation. They both have the same fine lines above water and both may be gaff-rigged or Marconi-rigged.

The story is that Joel was asked to design a small sailboat that was as beautiful and high-performing as the Herreshoff, but that could be transported on a two-wheel trailer between the customer’s residences at the lake and on the seacoast. Mission accomplished. (Primary image taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 28, 2025.)

It’s time for two September perspectives of the south face of that big, forested mound – that almost-a-mountain – that is officially named Blue Hill. Above, you’re looking roughly northeast at it over a rural landscape at mid-day. (See if you can find two totally disinterested horses.) Below, you’re looking virtually due north over Blue Hill Bay at low-tide on the same day:

The 934-to-940-foot high forested mound was called Blue Hill when mounds had to be at least 1000 feet tall to be called a mountain. That height standard has been abandoned and some people and institutions now call this Maine mound a mountain. But they have to call it “Blue Hill Mountain,” which seems as self-contradictory as calling someone a “boy man.”

Nonetheless, the mound called Blue Hill has nice hiking trails and views, especially in the fall. (Images taken in Blue Hill, Maine, on September 26, 2025.)

It all started when I went down to our ponds and saw a recently-felled young birch tree with its trunk cut in segments and wood chips all around. I suspected that this was not the work of a phantom forester.

The next day, most of that birch was gone and I went looking for it. I found it on a small island in our wild, bog pond, where it could be used as food, a lodge rafter, or both. We had received the mixed blessing of an American beaver on our place looking for real estate with a water view.

I finally saw him yesterday and the day before: He’s an adult between three and four feet long in good condition, as you see from the images here. If he attracts a mate and has a family, we’re going to have to worry about them blocking up our drainage culverts to dam and raise the water. If they do that, we’ll get a trapper to perform a beaver removal-and-release operation and take them for a ride to where they can be beneficial.

American beavers (Castor canadensis), not to be confused with Eurasian beavers, are the largest native rodents in North America. On balance, they benefit the environment by creating and filtering needed wetlands for other species.

These semi-aquatic mammals have webbed hind feet for swimming and self-sharpening incisors for felling trees. They’re most active nocturnally, use their broad tails as rudders and to give warnings by loud water slapping, and they can be pugnacious. Don’t try to touch one if you value having 10 fingers. (Images of the beaver taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 27, 202; sex assumed.)

Sailing in a small boat during a September sundown is special. Maybe it’s the soft, yielding sounds of the parting water as the light slowly disappears, or the feeling that you’re more in and of the water than on and riding it, or the sense of intimacy with the shifting wind, or just watching stars starting to appear in the vast, silent sky above and being filled with wonder.

(Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 24, 2025.)

Here you see a snowshoe hare venturing out at dusk Wednesday and looking like she just snuck a lick of vanilla ice cream. By the time of our first significant snowfall, this hare will have molted to virtually all white for camouflage. And, if recent years are any indication, she’ll be white before the ground is covered with snow, which is not good.

Our climate warming is creating less snow, but the snowshoes can’t seem to control their winter molts, making them almost glowing targets on winter nights when there’s no snow cover and sharp-eyed great horned owls, lynx, and bobcats are flying and prowling.

The hares’ large, stiff-furred hind feet become snowshoes and help them run and quickly change directions in snow. If it’s there. Nonetheless, they are fast, no matter what the terrain. There are reports of them being clocked at up to 30 miles per hour.

Maine has a somewhat similar species, the New England cottontail (NEC) or “cooney.” It’s a true rabbit; the snowshoe is not. Snowshoes have larger bodies, longer ears, and much longer feet than cottontails. Snowshoes also are common, while the NEC has become almost rare and is listed by the state as Endangered. (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 24, 2025; sex assumed.)

I recently commented about the abundant spring rain and numerous sunny summer days causing a profusion of orange American mountain ash tree berries here this September. Well, I discovered, about half a mile from the tree that I photographed then, this mountain ash that had a profusion of bright red (not orange) berries.

A little research indicates that this color variation apparently is fairly common for the American mountain ash (Sorbus americana, aka American rowan tree). Some of these trees have a genetic tendency to produce more red pigments (anthocyanins), while others produce more orange pigments (carotenoids). The amount of sun received, and age of the trees also apparently can affect their berry coloration.

(Images here taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 22, 2025.)

Some of September’s dramatic light and color effects can be seen by comparing this sunny vista showing the meadow atop Amen Ridge tinged in yellow goldenrod with the somber foggy view and the graying of the goldenrod two weeks later:

Those are Blue Hill and Jericho Bays in the foreground; and, in the distance, the mountains are on Mount Desert Island, Maine’s largest Island that includes most of Acadia National Park. (Images taken from Brooklin, Maine, on September 3 and 18, 2025.)

This apple tree on the WoodenBoat campus reportedly is over 100 years old and it still produces good looking fruit. (That’s the WoodenBoat Store behind the tree.) Part of the reason for this tree’s longevity has to be its hardy stock, another part likely is because it gets plenty of sun and tender loving care and is in a well-drained area.

The literature states that standard (non-dwarf) apple trees usually live from 60 to more than 100 years, depending on their care and environment. My guess is that this gnarly specimen is a Dabinett apple tree, a traditional English hard cider apple tree, many of which came over with Europeans who settled in Maine and Vermont. Here are a few images of its fruit:

Maine reportedly is home to well over 100 different apple varieties, with the Maine Heritage Orchard documenting over 300 distinct types of the fruit, some dating back to the 17th century. A Drap d’Or Bretagna apple tree, an heirloom French variety on Verona Island, Maine, is estimated to be more than 200 years old and one of the oldest apple trees in the state and North America.

The oldest known apple tree may be Isaac Newton's Apple Tree at Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire, England. Its remaining part is estimated to be over 370 years old and reportedly continues to produce Flower of Kent variety apples, which are best known as cooking and baking fruits. (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 22, 2025.)

As you can see, our crab apples are appearing in profusion, but they seem smaller than usual – more like berries than apples. Perhaps it’s the drought, or it’s too early, or it’s my imagination. Nonetheless, they’re a welcome visual addition to the dissipating garden. I should emphasize “visual”; these fruits are retchingly bitter. However, the red squirrels are eating them already.

There seem to be two theories as to why these apples were named “crab.” One is that they have a “crabbed” (i.e., disagreeable, nasty) taste. The other is that the name derives from the old Norse/Scottish/Swedish words for wild apple that sound like “crab.”

As it happens, our crab apple trees and many others are neither wild nor European; they’re ornamental, beautifully-blossoming, cultivated trees that originated in Asia. (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 21, 2025.)

The most frequently-heard September Song here does not contain poignant descriptions of getting old. It contains the surging baritones of a diesel engine accompanied by the grinding, hissing, and occasional clanging percussion of a rotary mower. Late summer and early fall are when many meadows and other fields are mowed here.

Here you see Dennis Black this week, doing the annual mowing of our meadows, a two-day job that is tricky in some places. It’s morning in our sloping north field, early enough to be before the fog in Great Cove has finished burning off. He already has finished our relatively flat south field. Both meadows are filled with two- and three-foot high wildflowers, grasses, sedges, and other vegetation that are in their September browns and whites.

By the way, as I understand it, a “meadow” is a specific type of fallow field that is not used for agriculture (except maybe hay in some cases), but that is allowed to naturally vegetate with non-woody plants. An annual cutting is necessary to prevent quick-growing raspberry bushes, trees, and other larger plants from reappearing and changing the density of the land cover.

We postpone the mowing of our meadows until the fall to assure that their summer residents – multitudes of birds, insects, reptiles, and other animals – are no longer raising their families there. Deer also sleep in them and members of “our” brazen herd will continue to do so, even now that their camouflage is gone.

Here are a few before and after images:

North Field Before (September 10, 2025)

North Filed After ( September 18, 2025

South Field Before (September 3, 2025)

South Filed After (September 17, 2025)

For equipment buffs: Dennis is riding an AGCO Allis 5670 tractor reportedly powered by a 244 cubic inch, four-cylinder, air-cooled diesel engine from the 1000 series. He’s pulling what I think is a Woods single-spindle rotary cutter. That type of cutter (or “mower”) commonly is called a “bush hog,” which is not quite correct.

A “Bush Hog®” is a brand name that should be applied only to the field and brush-cutting machines of Bush Hog LLC, headquartered in Selma, Alabama. (That company advertises that, when it first demonstrated its invention in 1951, an amazed farmer said: “That thing eats bushes like a hog.”)

(Mowing images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September 17 and 18, 2025.)

Above you see the 130-foot ANGELIQUE slipping quietly into Great Cove at sundown on Wednesday, where she overnighted. Thursday morning, her passengers rowed ashore in longboats to explore the WoodenBoat School, which is holding its last month of 2025 classes.

After the passengers rowed back to the vessel, alternating waves of fog and sun invaded the Cove in dramatic battle. ANGELIQUE waited, but eventually raised her four major sails in the fog; you couldn’t tell that they were uniquely tan-bark colored:

Just as she got her last topsail up, the fog cleared and ANGELIQUE pivoted to the north and departed the Cove. She raised her bow staysail and jib as she entered Eggemoggin Reach:shortly before noon:

ANGELIQUE is a gaff-rigged ketch (forward mast the taller) that was built for the tourist trade in 1980. She hails out of Camden, Maine, and was on a six-night cruise that included lectures by a historian and a naturalist, according to her schedule. (Images taken in Brooklin, Maine, on September17 and 18, 2025.)